Haloform formation in coastal wetlands along a salinity gradient at South Carolina, United States

Image Credit: [A. Chow]

Image Credit: [A. Chow]Abstract

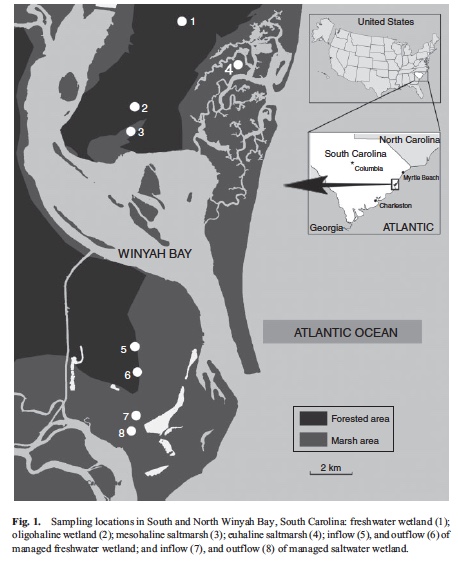

Soil haloform emissions are sources of reactive halogens that catalytically deplete ozone in the stratosphere but there are still unknown or underestimated haloform sources. The >200 000 ha of low-lying tidal freshwater swamps (forests and marshes) in the south-eastern United States could be haloform (CHX3, X = Cl or Br) sources because sea-level rise and saltwater intrusion bring halides inland where they mix with terrestrial humic substances. To evaluate the spatial variation along the common forest–marsh salinity gradient (freshwater wetland, oligohaline wetland and mesohaline saltmarsh), we measured chloroform emissions from in situ chambers and from laboratory incubations of soil and water samples collected from Winyah Bay, South Carolina. The in situ and soil-core haloform emissions were both highest in the oligohaline wetland, whereas the aqueous production was highest in mesohaline saltmarsh. The predominant source shifted from sediment emission to water emission from freshwater wetland to mesohaline saltmarsh. Spreading out soil samples increased soil haloform emission, suggesting that soil pores can trap high amounts of CHCl3. Soil sterilisation did not suppress CHCl3 emission, indicating the important contribution of abiotic soil CHCl3 formation. Surface wetland water samples from eight locations along a salinity gradient with different management practices (natural v. managed) were subjected to radical-based halogenation by Fenton-like reagents. Halide availability, organic matter source, temperature and light irradiation were all found to affect the radical-based abiotic haloform formation from surface water. This study clearly indicates that soil and water from the studied coastal wetlands are both haloform sources, which however appear to have different formation mechanisms.

Jun-Jian Wang thanks the China Scholarship Council (project number CSC[2011]3010) for financial support. We appreciate the valuable comments from Dr Alexander Ruecker at Clemson University. We thank Dr Vijay Vulava at College of Charleston and Dr Wayne Chao at Clemson University for help on halide measurement.We thank R. Zhu, S. Shen, J. Abad, P. Stow, A. Yu, Y. Zhou and S. Nagalingam for assistance with the GC-MS measurements and R. Weiss and B. Hall for gas calibration standards. This material is based on work supported by National Institute of Food and Agriculture–US Department of Agriculture (grant number SC-1700489), National Science Foundation (grant number 1529927 and grant number 1530375), and US Geological Survey Climate and Land-Use Change Research and Development Program. The work is presented in technical contribution number 6402 of the Clemson University Experimental Station